Updated: January 8, 2017

January 26, 2011. We received confirmation today that Albert Cooper has passed away. I had been aware that he had been in failing health for quite some time, but such is always sad news. Gareth from Jonathan Myall Music, and Just Flutes wrote us this morning, saying - in part - that: "He'd had pneumonia and lost the battle to clear it from his lungs.... We understand that he's had the best care possible recently and he had the ultimate in care during his last days. It's of some comfort that he's now at peace."

Albert had moved to an assisted care home and, over the years while there, had enjoyed frequent visits from Trevor Wye and many of Trevors students - and other devoted friends too - all of which had been a real source of joy to him for quite a while. Hearing that Alberts family were unaware of the great influence Albert had had in the "flute world", in early 2003 The Flute Network coordinated "The Albert Cooper Project" - we collected letters and stories from all who wanted to convey their own messages of thanks and tell of what Albert had meant in their lives. These were all organized into a scrapbook for him that I know Trevor Wye personally delivered. I remember hearing that it was well received at the time. (One of those things that - looking back - I'm so glad we did - all of us!) I know no further details at this time.

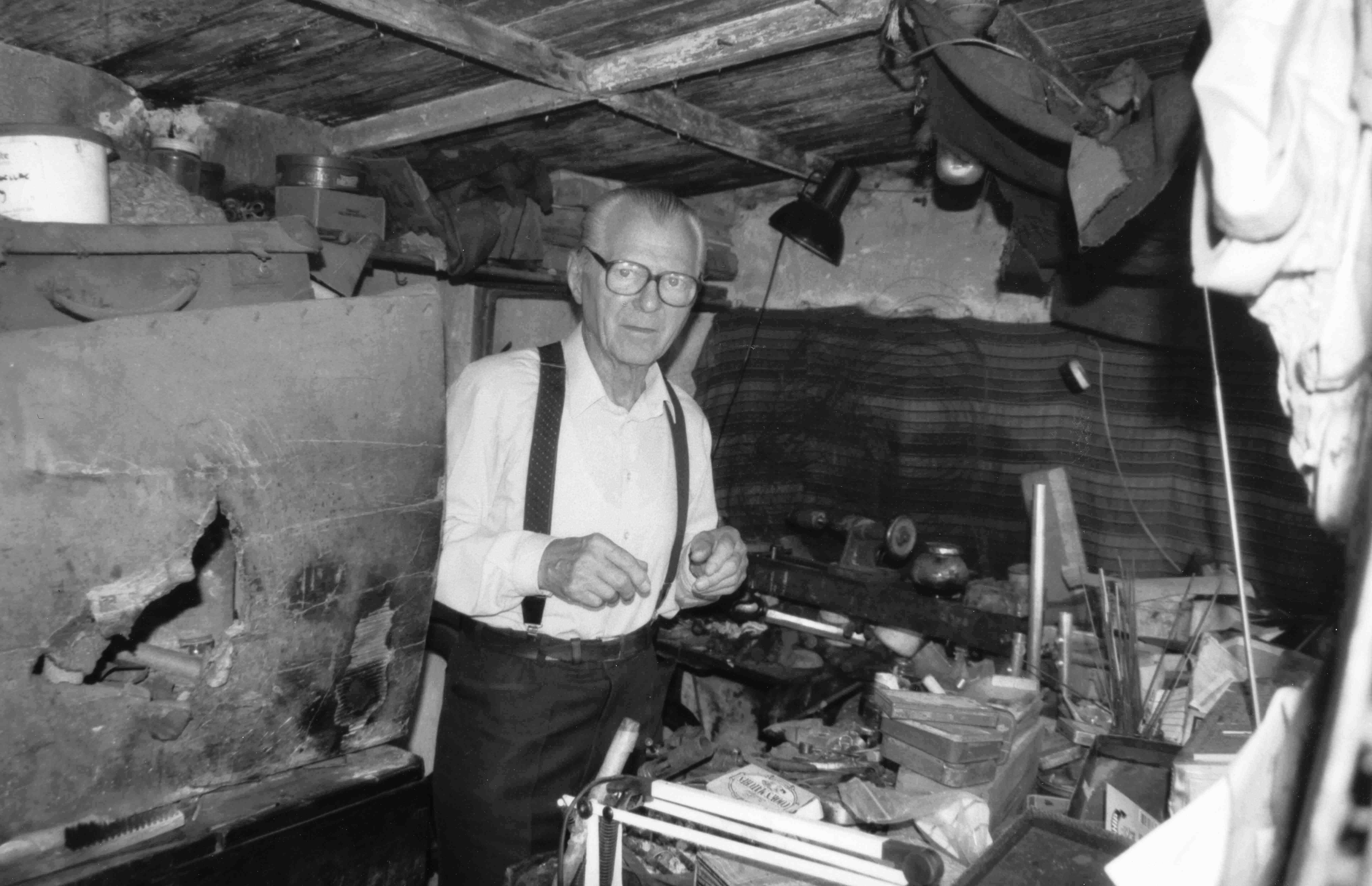

These pictures were made at Albert Cooper's place on the occasion of his 60th birthday. I remember the wonderful meal we shared, the stories I wish now that I'd written down, and all the laughter (Kate Lucas was there too!). Others will remember Albert for the magic he worked on their instruments and the legacy he has left the flute world. Visit the Brannen Brothers website (here: http://www.brannenflutes.com/news.html) - also the interview Alexander Eppler did with Albert in 1988 and has shared online here: http://www.epplerflutes.com/interview.html - for more about this man who I will always remember as being most warm and generous... and I'll add more here too as soon as I find my files and especially the journal I kept during that trip.

New - January 28, 2011. Trevor Wye has written a wonderful rememberance of Albert Cooper and sent along some terrific early pictures - it's an honor to have his permission to share it all with you here: .

Albert Cooper’s reputation and influence was worldwide, creating flutes of the highest mechanical excellence, establishing alterations and additions to the keywork of traditional flutes, but more famously, to their scales. The term, Cooper’s Scale has become part of our flute talk.

Cooper worked in such a straightforward way, with basic handmade tools and uncomplicated explanations. Flute makers for many years had enjoyed an almost sacred reputation, not completely deserved, of knowing all there is to know about their art. Cooper's use of a severed tree trunk, a hammer, reducing rings and a strong arm showed that anyone could make headjoints if they chose. His tools, now cared for by the British Flute Society, are very plain and mostly consist of disused metalwork files which have been polished and sharpened, and custom-built tools for holding tightly a small piece of keywork while he worked on it. On his retirement, he looked at the collection of a lifetime’s tools on his bench and said, quite accurately, ''Flute making tools? It’s really just a pile of old junk''

Flute makers who visited him and learned from his ideas such as the flute maker, Rainer Lafin, said recently, 'Albert taught me everything.' His engineering skill was incredible because he worked to great accuracy which is why his flutes played so well and were admired as pieces of engineering excellence. He also altered the design of keywork so that padding was more reliable and longer lasting. He learnt the broad principles of metal engraving by ‘watching someone’ after which he went to an evening class just to see a different approach and then made his own engraving tools from steel scrap.

Cooper was proud of his skill with the most fundamental tools, almost to the point of obsession, his aim being to make flute parts using the simplest means. He much preferred to use primitive tools perhaps because he felt he had greater control over them that he would with multi-task lathe or a classy pillar drill. He frequently boasted of his use of a potato to make key riser castings, though he certainly used the steam from a hot potato to force the molten silver to fill the crevices of the mould. Even so, he still had castings made up for him by specialists. So where was his skill? Undoubtedly, it was his ‘eye’ for elegance and accuracy combined with his unruffled control and application of workshop tools; that’s where his great skills were evident. He could see where a mistake had been made, or quickly spot an erroneous key shape. That, combined with his patience to complete a task to a high degree of accuracy and beauty using just his bare hands, those were his great skills.

Any attempts to engage him in general conversation other than flute matters was not very productive. His only real interest was the flute and its construction and though he read the newspaper daily, he never commented about what he read and accepted life as it came, without complaint. A late plane or even the occasion when he was mugged in a New Orleans street during an NFA Flute Convention, didn’t particularly give him cause for story telling. Once it was over, he just accepted the event as part of life’s rich tapestry. He enjoyed simple food too, and when asked if he would like some wine, usually replied, ‘Yeh, I’ll have a drink ‘o wine’. He was ambitious in his aspiration to be a fine flute maker and one assumed that his spare moments were directed only towards the flute and its construction.

Albert Kendall Cooper was born in Hull, England in 1924. An only child, he attended Pollard’s Hill School in Streatham and was a good student who never missed school or played truant. Albert was not a ‘good boy’, he just naturally conformed to whatever the rules and regulations required. School was not a particularly happy memory because, with his northern accent, he didn’t fit in well, He was told to say ‘Friday’ instead of ‘Fridee’ ‘It’s trivial really, but it hurt at the time’, he remarked and the other boys teased him about his accent and pronunciation.

At school, he was talented at metalwork and woodwork, but poor at all other subjects. At his last year at school, he began playing the saxophone and clarinet, though, as he admitted, he never reached a very high level of playing. It was a good hobby and enabled him to play in local bands and occasionally in local theatres for shows such as those that were staged at the Theatre Royal in Streatham.

Early in 1938, Albert's father went to the famous London flute makers, Rudall Carte & Co. at 23 Berners Street, Soho, to have his flute adjusted and while he was there, the showroom staff mentioned that there was a shortage of flute makers in the workshop, so Albert applied to become an apprentice and was accepted. He left school at the earliest possible date, Easter 1938, and signed the Articles of Apprenticeship to work there until he was 21 years of age, this being the norm. However, after the outbreak of World War Two, Albert was called up to join the army which he did in 1942, so his apprenticeship agreement had to be broken. He joined the Rifle Brigade in York and he was surprised to be told that he was being transferred to the Royal Navy. He then trained as a telegraphist, learning morse code and signals. Albert was a known as a ‘Telegraphist TO’, a Trained Operator. Within a short time, he was sent off to Greenock, Scotland, where he embarked on the passenger liner, SS Erontes destined for Malta. From there he spent most of the war in Italy, which later inspired him to learn Italian.

Before the second World War, Rudall Carte had about 16 men working in the full workshop. High pitch went out and players had to buy the new low pitched instruments and so flute making was flourishing. The wooden flute workers on the ground floor also made five-keyed Bb military fifes for which Albert made the keywork but not the bodies, as he never worked with wood. In between sweeping floors, making small parts and generally making himself useful, he watched the workman at their various tasks, and in this way, he learned flute making. It was part of the tradition at the works that everyone had a nickname, and Albert was always known as Harry Brown, or Harry for short. After the war, he was discharged and returned to his home in Stockwell, and then returned to his old position.

Back at Rudall & Carte, there were only three of the former workmen remaining, and it was very difficult for the company to get the orders going again because of the 50% Purchase Tax on flutes, making them prohibitively expensive to all but the well-off.

To his co-workers, Albert was a quiet individual who said little. He walked into work one Monday morning, and declared, ‘I got married Satdee’. Just like that. They were all so surprised. He would come out of the workshop at the end of the day and run to get his bike. When not on his bike, according to his co-workers, Albert used to run everywhere. He commented later, ‘I don't remember running everywhere, but walking seemed a waste of time!’ He had married Olive McLewee and after two other addresses moved to 9 West Rd, Clapham, the house where he remained for the rest of his life, and where he built his now famous workshop. This was ostensibly a small shed in the garden where he sat working whilst the visitor only had room to stand at the door to watch him.

At Rudall & Carte’s, Len Hind, the foreman, was approaching retirement, and thought the company would probably offer Albert the job. Albert preferred to work at the bench and didn’t want promotion, nor even to be asked, so he thought it better to leave. He left in 1959 to start a repair service but quite soon after, began making flutes and headjoints. Initially, he would have copied the designs he knew well, but the stream of London players who visited him for alterations, repairs and modifications soon had him experimenting with design. He carefully examined any new flute or head joint that was shown him, so gaining ideas from other makers.

Meantime, Olive, Albert’s first wife died of a complication of her condition, diabetes, on 20th May, 1974. His second marriage to Philomena Burns, ‘Mena’, took place on 17th September 1977.

When he moved to 9 West Rd, a steady stream of well known London players visited him for a assortment of reasons. In the beginning, it was to order a flute to be made but also to have repairs, but as ‘the scale’ because famous, he began retuning old French and modern American flutes. His headjoints became more sought after, and became a good source of income. William Bennett, Elmer Cole, The Taylor brothers, Christopher and Richard, Alex Murray, London Symphony Orchestra players, and others, consulted with Albert whose house became a repository of flute information, especially regarding the latest scale information.

Elmer Cole and William Bennett both contributed to Albert’s search for a true scale on which to build our flutes and were in fact largely responsible for the calculations which resulted in what became known as Cooper’s Scale. As ‘the Scale’ developed and players offered their opinions, Cooper updated his figures and gave the latest revision to anyone who asked for it. Over time, he gave different scale figures to different makers. Just a few years ago, he said: ‘Cooper’s Scale? What’s that? There isn’t ‘a’ Scale. There is a constant revision taking place so that, at any one time, there is a set of figures which you can use to design your flute, but these will change in the light of experience. I altered the scale a little as the years went by, mostly according to certain criticisms levelled at it. I now feel that I have more or less reached the end of the road scale-wise.’

His unvarying search for excellence and his dogged determination to give flute players a reliable scale resulted in his mounting reputation until his skills became legendary. Albert could be seen at Flute Conventions discussing the latest in key design or mechanism with flute makers all over the world. He was always willing to help, advise, or offer figures to anyone who asked for them, often to the astonishment of his flute making rivals. Albert was naturally big-hearted and would share anything with anyone. His legacy is that he was the greatest influence on our instrument since Theobald Böhm. He set a standard for mechanical excellence, he redesigned our scale allowing us to be more expressive, he gave makers new ideas and additional keys to make our performing lives easier and he set an example of generosity. This humble man showed that we are merely caretakers of the knowledge we acquire in our lives and he set the example that we should pass this on freely to anyone who wants it.

A few years ago, he became unable to look after himself at home and moved to a number of nursing homes, Mena also joining him where she died about 3 years ago. A couple of days after Albert’s 80th birthday, he was asked, ‘You are such a famous man. There is hardly a flute player anywhere who hasn’t heard the name of Albert Cooper.’‘Well,’ he commented, ‘I dunno why. All I’ve done all my life is tinker about with flutes…’

© Trevor Wye 2011

Totally thrilled to get to add the folling note from Jeff Cook, as arrived here January 7, 2017 -- and I'm hoping he may write more about this! In the duration, this tidbit is joyfully shared, with his permission. When someone as influencial as Albert Cooper leaves such a legacy, it's always fun to consider how it resonated further in the world, much like this.

Hello Jan.

I`ve just found your piece on Albert Cooper by Trevor Wye and was slightly surprised there was no mention of Boosey & Hawkes, Edgware, London, so I thought I`d drop you a line.

I used to work at B&H from 1972-2000, when the factory closed, the land it stood on is now a housing estate. I worked on many different projects over the years but the best time was when I was responsible for making clarinet mouthpieces (952-1010) and sterling silver flute heads (925) to the Albert Cooper design. I remember doing three months training with one of the craftsmen, a great bloke who knew Albert well, Ron Spackman. All the work was done by hand and at peak production I think I was making about 50 to a 100 flute heads a week, depending on requirement.

I was introduced to Albert just once, there was talk of going to his workshop/garden shed but unfortunately it never happened. I think my work was good enough as I never got any complaints from him. All the heads were etched with the B&H logo plus the Cooper name. It was a great job and quite well payed for the time. There used to be a small museum on site, it had lots of very old and rare instruments of all types, not sure if any were Albert`s early works though. The whole museum was given to the Horniman museum in south east London (website should be available).

Email:jan@flutenet.com.